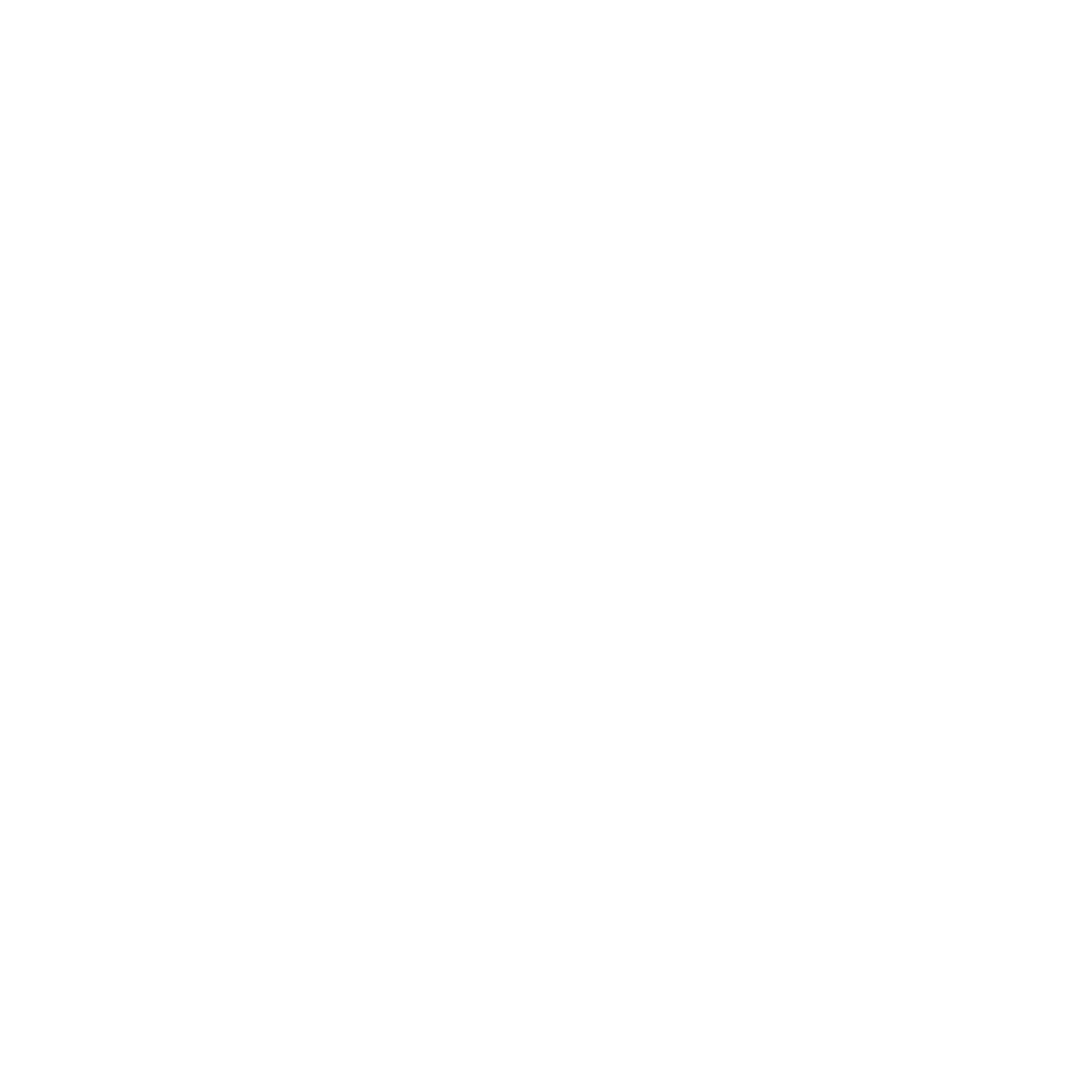

How to Weave a Rope Trivet

There is something deeply gratifying about using an object that you have made yourself, because that object becomes more valuable to you. But when was the last time you truly took the time to slow down, unwind and create something for yourself? This week on the Butser blog, our intern Natasha takes us through the mindful art of weaving rope trivets - just in time for our rope trivet workshop in March!

A Brief History of Rope Making

Long before machines and mass production existed, rope was made by braiding or twisting rope-like vegetable fibre or animal hair. In prehistoric times, it was essential for fishing, as well as gathering and capturing animals. Later, the Ancient Egyptians developed rope making tools, since rope was essential for moving heavy building materials.

In western Europe, from the thirteenth century onwards, rope was made in factories called ropewalks - long buildings where fibres were laid down and twisted together to make one rope. At the time everything was operated by hand, although that changed after the industrial revolution. Over the centuries, rope making techniques have continued to change, but the importance of rope itself has never diminished. It remains deeply essential even today, particularly in the nautical world, in construction, and even in everyday life.

Today, traditional rope making is considered an endangered heritage craft. Thanks to Sue Pennison - a traditional rope maker, yacht rigger and Chair of the Trustees of the International Guild of Knot Tyers - visitors to Butser can take part in one of our Woven Rope Trivet Making workshops this March, to help keep the knowledge alive through hands-on practice.

An Introduction to Sue Pennison

Sue Pennison is a lifelong sailor, sailing on the Norfolk Broads as a child and learning a wide variety of knots during her lifetime. Dissatisfied with the range of cord she could buy, however, she decided to buy a rope maker and start making her own! In her eyes:

‘Rope making and knot tying has been an intrinsic part of human life for thousands of years. Under guidance, the elegant simplicity of the process allows people of all ages to get ‘hands on’ and make quality rope and cord. Then there is the joy of turning it into something practical and beautiful.’

About the Workshop

The workshop will take place on 22 March 2026 in our Roman Villa. You’ll not only be stepping into the past by learning a traditional craft, but by experiencing it within the walls of our Roman building - immersing yourself in what it would have been like to live in the past.

During the workshop, you will be able to make your own natural hemp rope using a hand-powered mechanism, as well as creating a traditional heatproof rope trivet with the rope you will have crafted!

This female-led session will be relaxed and welcoming for all participants, regardless of prior knowledge or experience. At the end of the workshop, you will leave with a finished piece that’s both functional and satisfying to use in your own home.

There are two sessions available:

The morning session from 10am - 12.30pm

The afternoon session from 1pm - 3.30pm

Ready to try your hand at a heritage craft? Click here to learn more or sign yourself up to the workshop.

WOVEN ROPE TRIVET WORKSHOP

with heritage ropemaker Sue Pennison

Saturday 22 March 2026

Half-Day Workshop: 10am - 12.30pm OR 1pm - 3.30pm

Create a traditional rope mat made with a natural hemp rope (formed by participants during the session). Approx 20cm diameter. Heatproof for domestic purposes.

Relaxing & welcoming, female-led & beginner-friendly, small group size.

Set in the unique surroundings of a recreated Roman Villa!

Twist, Cut, Weave: Why Hedgelaying Still Matters

Over the last two weeks, we’ve been given the fantastic opportunity of holding a hedgelaying course thanks to funding from the East Hampshire District Council Grow Up! Fund. But what exactly is hedgelaying, and why is this traditional craft still relevant today?

What is Hedgelaying?

Hedgelaying is a traditional countryside craft in which the stems of shrubs or small trees are partially cut and carefully bent over to lie at an angle. These stems are laid along the line of the hedge to create a dense, living barrier. Over time, this process encourages fresh growth from the base of the plant, resulting in a thicker, healthier hedgerow. Unlike simple trimming, hedgelaying keeps the hedge alive and thriving. It has been practiced in the UK for hundreds of years, and different regions have even developed their own style variations.

The Importance of Hedgelaying

Hedgelaying plays an important part in wildlife-friendly agriculture. It acts as a natural barrier for livestock and crops, effectively providing an alternative to modern fencing. Environmentally, hedgerows help prevent soil erosion, reduce flooding and wind damage, as well as providing shelter, food and nesting sites for birds, insects and small mammals. Passing on hands-on knowledge and skills is also becoming more important in an increasingly digital world, and teaching hedgelaying helps preserve and pass on our cultural heritage for future generations.

About the Course

Our hedgelaying courses are led by Darren Hammerton, an expert treewright and hedgelayer. Thanks to Darren, the attendees were able to learn all about hedgelaying in our idyllic landscape, surrounded by nature and listening to the sounds of rustling leaves, birdsong and the crackling of the fire.

Our placement student Natasha observed the course this week and talked with one of the attendees, who said:

‘The course is really enjoyable. I learned a lot from Darren, the learning environment is great, and I loved working with traditional tools and products.’

Thank you again to the East Hampshire District Council Grow Up Fund that made these courses possible. Opportunities like this not only help people develop practical skills, but also strengthen community connections and revive knowledge of ancient crafts.

The East Hampshire District Council Grow Up! Fund

The Grow Up Legacy Programme is an East Hampshire-wide programme that funds community groups in order to run events that promote employment, education, volunteering opportunities and that strengthen engagement in East Hampshire. We recently received funding from the Grow Up Legacy Programme, set up by the East Hampshire District Council, that enabled us to host two four-day long hedgelaying courses. We are very grateful for the funding we have received since we were able to welcome 24 people across both weeks free of charge. This allowed people from all backgrounds, regardless of their prior experience, to come together and gain valuable knowledge.

If you would like to learn more about hedgelaying, you can watch Darren at work on a previous hedgelaying course through our YouTube channel below:

How to Throw a Lupercalia Pancake Party

Who doesn’t love Pancake Day? Hovering on the cusp of spring, a sanctified invitation to dine on sugar-sprinkled stodge for breakfast, lunch and dinner. But did you know that Shrove Tuesday, like so many Christian celebrations, actually has pre-Christian roots? In holy lore, Shrove Tuesday (also known as Mardi Gras or ‘Fat Tuesday’) is a time to confess your sins, burn last year’s palm leaves, choose something to give up for Lent, and eat pancakes, sweets and other rich foods before fasting for 40 days. The theme is purification, just like its pre-Christian predecessor: The Ancient Roman festival of Lupercalia.

The Romans observed Lupercalia every year to purify the city, promote health and boost fertility. The purification instruments used, known as the februa, gave the month of February its name. It coincides with the purification we see in the natural world as February marks the end of winter, when old life sinks into the earth and new growth begins again. It’s a time to purge unwanted thoughts and behaviours, and welcome in a brighter, warmer kind of energy. The Romans called this festival Lupercalia in honour of Lupercus, the Roman god of fertility. In the creation myth of the founding of Rome, Lupercus helped the she-wolf take care of Romulus and Remus, which is why Lupercalia was also a celebration for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

In true Roman fashion, Lupercalia was said to be a booze-fuelled festival of feasting, mating and merrymaking, after which the participants would fast for 40 days. Rituals were held in the Lupercal cave, the Palatine Hill and the Forum, all of which were important locations in the story of Romulus and Remus. Near the cave stood a sanctuary dedicated to Rumina, goddess of breastfeeding, and the wild fig tree, whose pendulous, milky fruits were likened to breasts. The day’s rituals were facilitated by a priesthood called the Luperci or ‘brothers of the wolf’, and included the sacrifice of goats and dogs, a sacrificial feast to follow, and a naked jog around the block carrying the flayed skins of the animals. These were used as whips to strike pregnant and barren women in the hope it would boost their fertility.

This year, as you’re sprinkling sugar and lemon on the fifteenth pancake of the day, consider taking your Pancake Day celebrations back to Ancient Rome by trying a Lupercalia ritual for yourself!

How to Throw a Lupercalia Pancake Party

1. Find a cave with wild fig trees growing outside. Decorate.

2. Choose a nice corner in which to make a Lupercal altar.

3. Invite friends, family, breastfeeding women and ancient priests to join.

4. Approach the altar and sacrifice two male goats, a dog and a plate of salted mealcakes pre-prepared by virgin priestesses.

5. Anoint guests with sacrificial blood, then clean knife with wool soaked in milk.

6. Everyone laughs.

7. Ask priests to cut strips from the animals’ skin.

8. Invite guests to remove their clothes and run naked around the nearest hill carrying the strips of skin. Strike anyone who approaches, particularly pregnant and infertile women.

9. All guests return to cave for pancakes.

What’s On this Half Term?

Star trails over our Iron Age village - photo by Greenglow Photography

In the face of wintery weather, there’s nothing better than soaking up the atmosphere of our ancient houses, meeting our rare breed animals, stretching your legs in the fresh air and sipping hot chocolate with a view over the South Downs.

Opening Times

Saturday 14 Feb - Sunday 15 Feb

(Closed Mon 16 & Tue 17)

Wednesday 18 Feb - Sunday 22 Feb

Open 10am - 4pm

Pre-book your tickets to save £1 per ticket!

This half term, we are celebrating Dark Skies Week with a FREE celestial-themed family trail! Follow the Stars will take you on an ancient journey under the sky. Discover more about how ancient people used the sky above to find their way around the world, and hunt for golden stars around the farm to complete the missing word.

You can also make willow star wands and sun disc pendants to take home, play with Roman boardgames, mosaics and Saxon runes, and meet reeanctors from across the ancient world. Plus, have a go at archery over the weekend of 21-22 Feb!

If you’re looking for last minute holiday clubs for school-age children, we also have a handful of spaces left on our Time Traveller Holiday Club! Your child will experience Butser like never before, spending each fun-filled day with us packed with exciting activities, from making their own clay pots, grinding wheat and baking bread, to trying out weapons, playing ancient games and getting to know the Butser goats - all in the beautiful setting of our ancient buildings in the Hampshire countryside!

For the adults, why not celebrate the new moon with our Lunar Connect & Reset evening yoga circle on Friday 13 February? Reset, recharge and welcome in fresh intentions for the month ahead with our brilliant yoga teacher Holly Hayward. Ground yourself by the fire in our Great Roundhouse, and take the time to check in with your body and your mind. Through gentle movement and reflective practices designed to inspire creativity and self-expression, relax and recharge as the moon begins its cycle anew.

One more thing! Half term visitors from Wednesday to Friday may spot a few industrious workers laying a hedge along the Butser pathways. This course has been offered free to locals through funding by EHDC’s Grow Up! fund. If you’re interested in the traditions and ecological benefits of hedgelaying, you can also watch the video below via the Butser YouTube channel, featuring our excellent treewright Darren Hammerton as he takes us through the stages of laying a hedge.

WIN A BRONZE AXE HEAD!

To celebrate the relaunch of Butser Plus, we are giving away this beautiful bronze axe head made by our resident archaeo-bronzesmith Jim Clift.

This piece is based on an early Bronze Age flanged axe, similar to those in the Arreton Down hoard, excavated on the Isle of Wight in the eighteenth century. In 2012, an English Heritage report even used laser scanning to discover dozens of these axe shapes carved into the stones at Stonehenge!

TO ENTER: Sign up to our Butser Plus platform at any tier between now and 28 February!

This can be a monthly or annual subscription, but must be placed before 23:59 (GMT) on 28 February 2026. At the end of the month, we will choose one lucky winner at random and post their prize to them anywhere in the world. Click here for the full terms & conditions of this prize draw.

Building Butser’s ‘Little Hadrian’

John at work on the wall

The Experimentalists are an exciting volunteer team here at Butser, working on experimental projects to bring our ancient houses to life. They’re currently working on several projects across the farm. In this update, Margaret Taylor (Experimentalist and volunteer librarian) shares a short update on the team’s progress.

Butser Ancient Farm has a reconstructed Roman Villa, based on the one found at Sparsholt, Hampshire. At the front of the Villa there is a beautiful Roman garden, complete with a mosaic and stone seating area, and on the western side there is a flourishing kitchen garden. However, the area between the western Villa wall and the kitchen garden requires attention. The mission is to create an attractive useable area where the Villa inhabitants and visitors can relax.

Therefore, in June last year Butser staff enlisted our team, the Experimentalists, and trained us as ‘Roman soldiers’ to build the western boundary wall. There was already a low wall there; when the Roman Villa was built, it was a training area for new recruits. When they had passed the ‘skills test’ on that wall they were free to use their new found skills on the actual Roman Villa.

Preparing the mortar

Butser staff kindly managed and trained us, provided us with PPE and also provided us with some excellent buffet lunches, as a reward for our work. Building the wall has been a particularly enriching experience for John. He has ‘found his calling’ and would have continued building the wall at his home, if that was possible! It has been an enjoyable and challenging ‘learning curve’ for all of us. Retaining walls need to be strong; a pretty face is not enough. Hadrian’s Wall is still standing - and Butser’s own ‘little Hadrian’ needs to stand the test of time too.

The wall is constructed with a flint and lime mortar. Lime mortar is a traditional building method, which is flexible, allows for movement, and is moisture resistant and durable. We used a ratio of two spades of lime to three spades of sand. We also had to correctly add the appropriate measure of water, with the result that the mixture varied. We had minor set-backs; occasionally, the mix was less good or the wall got wet before the mortar set. Consequently, with the great British weather, we often had to cover the wall with a variety of modern tarpaulins. Crucially, if we did not adhere to ‘flint on flint’, some sections of wall crumbled and we had to redo them. But set-backs have been minor and we have progressed well; the first few metres of the wall are complete and we have now reached the far end of the Villa. So far, we have used 7 tonnes of flint! However, winter has stopped play, as the temperature is required to be 5° C or more, otherwise the mortar will not set.

Roman Soldiers on Hadrian’s Wall would have had the advantage of large numbers of men, and they would have had to work in shifts until the wall was finished. They certainly wouldn’t have been visiting the wall once a week! Would they have completed all the work in good weather, or continue through bad weather?

However, as modern ‘soldiers’ we are spending the winter completing other Butser tasks, retreating to the inside of ‘our’ Iron Age roundhouse (Danebury CS1), sitting around the fire and waiting for summer to arrive so that we can finish ‘our wall’. We will of course, keep readers informed of our progress!

Further study: The Winchester City Museum is an excellent place to visit and discover more about the Roman Villa at Sparsholt.

Update by Margaret Taylor and John Briggs, from The Experimentalists.

Consultation with Maureen and Imogen

The first section of the wall is now finished

Win a Bronze Axe Head with Butser Plus!

We have a special announcement to share today! If you’ve been following us for a while, you may have heard of Butser Plus - our supporters’ platform that helped us survive the pandemic and create a library of videos about our archaeological experiments.

After four years in its original form, and with everyone slowly getting back to normal after lockdown, we are delighted to be reshaping and relaunching Butser Plus with a couple of exciting changes.

↓ Keep reading to find out more about the past and future of Butser Plus, how we plan to keep thriving - and how you could win this beautiful Bronze axe head!

The Birth of Butser Plus

Back in 2021, the farm was reeling from the effects of months of lockdown in the wake of the global pandemic. As a not-for-profit site, we were affected badly by the loss of visitors. If we had continued down the same path, it would have been impossible to stay viable, given that it cost £800-£1000 a day just to keep the farm running, maintain the buildings and feed the animals.

Fortunately, our team never give up. Together, we came up with the idea for a brand new online platform that could help counter the income loss and protect our future, while at the same time using modern, global techonology to provide a connection back to our ancient past for everyone else confined to their homes.

Hollie filming metallurgy for Butser Plus

The result was Butser Plus - an online platform that would allow users to enjoy professionally shot, behind-the-scenes video content about life at our unique heritage site. Supporters from around the globe were able to access exclusive content, and their donations helped safeguard the farm’s future as it recovered from the impact of the pandemic. The project was further aided by funding from the UK Government Culture Recovery Fund, recognising how online tools can be used to help people stay connected.

To create our video content, we are lucky to have onboard Hollie Osborn, a highly accomplished producer and director, and the face behind the camera capturing all our incredible video footage. Hollie has worked on a variety of shows including the Attenborough series Africa, BBC One’s Farmer’s Country Showdown, and Channel 5’s Funniest Pets at Christmas (so she has no problem handling our rare breed animals!). Hollie’s expertise and keen eyes are what has allowed us to bring the essence of Butser onto your screen and into your home, wherever that may be.

Prof Alice Roberts taking part in our Bronze Age build project, documented as a multi-part series for Butser Plus

The Future of Butser Plus

Five years on, and we are relieved to say that Butser made it through the worst impacts of the pandemic. But with one crisis over, another looms - in the shape of an ever-changing heritage industry. The UK heritage sector is facing a significant and ongoing struggle, with some statistics pointing to an ‘existential threat’ driven by a combination of funding cuts, rising operational costs and post-pandemic challenges. As an independent, not-for-profit heritage site, we take our responsibility seriously to keep Butser thriving in the face of adversity, and we pride ourselves on always thinking ahead to future-proof our 50-year-old, pioneering project.

The core Butser Plus team - Hollie (left) and Tiffany (right). You can find out more about them here!

Free Videos for Everyone!

With this in mind, we have made the decision to release our entire Butser Plus video library - free of charge - so it can be accessible to everyone! This means taking all 100+ videos out from behind the paywall and uploading them to YouTube over the next few months, as well as continuing to create and upload brand new monthly videos going forward. These videos are something we are incredibly proud of, and as a site dedicated to accessibility, education and broadening the knowledge of all, we are really pleased to be releasing these to a global audience - all for free. We wouldn’t be in a position to do this, of course, without all the people who have supported Butser Plus since it launched in 2021. We cannot thank you enough for all your contributions, which have not only funded our videos, but have kept the entire farm afloat in an incredibly unstable and troubling time.

On seeking feedback from our supporters, we found that a large chunk of Butser Plus members choose to support us out of generosity alone, regardless of other perks and benefits. Many people recognise the pressure put upon the heritage industry, and in the age of Patreon-style platforms, we have been humbled by how many of you are keen to support us with a monthly or annual donation - just because you love our work. In light of this, we are moving our Butser Plus platform over to our website so that everything is in one place, making it even easier and more convenient to support the farm with a regular donation. Pioneer and Hero supporters will still have early access to Beltain and Equinox tickets, and we’ve launched this brand new behind-the-scenes blog that will take you into the heart and soul of the farm. We will also be adding links to all the content in our Video Library so you can see everything in one place.

We are so excited for the future of Butser Plus, and we continue to be extremely grateful for every single person who chooses to support the farm through a monthly donation. Without you, we wouldn’t be able to keep producing such fantastic videos - and we can’t wait for even more people to see the collection, now we are releasing them for free.

How Can You Get Involved?

To support Butser Plus and help us future-proof our pioneering ancient farm:

Join Butser Plus and receive early access to Beltain & Equinox tickets, plus a monthly behind-the-scenes blog post exploring everything from building plans and archive photos to animal births, archaeological experiments and the rhythms of farm life in the beautiful South Downs.

Subscribe FREE to our YouTube channel and enjoy hundreds of videos about our archaeological experiments, rare breed animals and everyday life at the farm.

Win a Bronze Axe Head!

To celebrate the relaunch of Butser Plus, we are giving away this beautiful bronze axe head made by our resident archaeo-bronzesmith Jim Clift.

This piece is based on an early Bronze Age flanged axe, similar to those in the Arreton Down hoard, excavated on the Isle of Wight in the eighteenth century. In 2012, an English Heritage report even used laser scanning to discover dozens of these axe shapes carved into the stones at Stonehenge!

TO ENTER: Sign up to our Butser Plus platform at any tier between now and 28 February!

This can be a monthly or annual subscription, but must be placed before 23:59 (GMT) on 28 February 2026.

At the end of the month, we will choose one lucky winner at random and post their prize to them anywhere in the world.

See below for the full terms & conditions of this prize draw.

Bronze Axe Head Prize Draw - Terms & Conditions

Promoter

The prize draw is promoted by Butser Ancient Farm (“the Promoter”).Eligibility

The prize draw is open to individuals aged 18 or over. Employees of the Promoter and their immediate family members are excluded.How to Enter

To enter, participants must hold an active subscription to Butser Plus at any payment tier during the period 1–28 February 2026. Only one entry per person is permitted, regardless of subscription tier.Entry Period

Entries open on 28 January 2026 and close at 23:59 (UK time) on 28 February 2026.Prize

The prize is one bronze axe head, as pictured and described above. No cash alternative or substitution is available.Winner Selection

One winner will be selected at random from all eligible entries on 1 March 2026.Winner Notification

The winner will be notified by email using the contact details associated with their Butser Plus account. If the winner does not respond within 14 days, the Promoter reserves the right to select an alternative winner.Delivery

The prize will be posted to the winner at no cost, to an address provided by the winner, anywhere in the world. The Promoter is not responsible for customs delays, import taxes, or duties.General

The Promoter’s decision is final and no correspondence will be entered into. By entering, participants agree to be bound by these Terms & Conditions.

Experimenting with Iron Age Tapestries

The Experimentalists are an exciting volunteer team here at Butser, working on experimental projects to bring our ancient houses to life. They’re currently working on several projects in our Iron Age village. In this update, Margaret Taylor (Experimentalist and volunteer librarian) shares a short update on the team’s progress.

Our loom, warped and ready to go, constructed by one of our team, Alan. Photo by Margaret Taylor.

Since our last blog, the Experimentalists have been really busy with a number of projects: enhancing the CS1 roundhouse, rebuilding the Iron Age toilet, and of course building the Roman Villa wall. These will all feature in future blogs, but this entry is about our spinning project.

Readers may remember my early battle with drop spinning. I am now pleased to report that I have improved - but definitely not mastered the process! I have shared the skill with the team, and we have now been inspired to create a tapestry picture, depicting a view of one of the Butser Iron Age roundhouses, with the hills as a backdrop.

But did our Iron Age ancestors make tapestries? Of course, we do not know, as very little survives. However, they were accomplished weavers, making clothes, and they would have wanted to make their homes cosy and warm. We, the Experimentalists are based in CS1 - one of the Danebury roundhouses - and we know that at Danebury our ancestors were definitely spinning, and using their spun wool to weave. Elizabeth Wayland Barber (author of Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years) also tells us that in the Bronze Age ‘Greek women sometimes did produce storytelling cloths and some of these ‘tapestries’ were kept in the treasuries of Greek temples.’

Dyeing itself has very long roots, although in the Iron Age, Nicole DeRushie (author of Bog Fashion: Recreating Bronze and Iron Age Clothes - available in the Butser shop) describes how ‘white wool was quite rare in the early Bronze Age, becoming more common as centuries wore on and breeding coaxed out this colour, which is best for dyeing.’ By the time we reach our period, the Iron Age, dyeing was popular and woad was certainly popular, both for painting bodies for warfare and for transforming textiles.

As a group, we have been experimentally dyeing with oak bark, tansy, weld and others. Maureen has been busy using natural dye stuffs from her garden, including tansy and oak, and spinning her wool. I hosted a small dyeing workshop in my garden. A small group of the team used weld (commercially purchased), consulting Jenny Dean’s Wild Colour: How to Make and Use Natural Dyes to create 20 different shades of green from one ‘dye bath’ using different mordants. We have also experimented with woad - this grows at Butser but I used woad from my garden. Woad produces shades of blue, but the process is tricky and we were not successful. Further research and practice are required and we will try again in the summer. Meanwhile, the team are keeping busy spinning more wool and we hope to begin weaving in the summer.

Our weld experiments. Photo by Margaret Taylor.

Spinning. Photo by Belinda.

REFERENCES

Elizabeth Wayland Barber - Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years

Barry Cunliffe - Danebury Hillfort

Jenny Dean - Wild Colour: How to Make and Use Natural Dyes

Nicole DeRushie - Bog Fashion: Recreating Bronze and Iron Age Clothes

What Was It Like to Sleep in a Roman Villa?

Salvete! In this wintery edition of our educational newsletter, we are exploring all things Romano-British. Did you hear about the new Roman villa they’ve unearthed in Wales? What was it like to have a Roman sleepover? And how do you recreate an ancient mosaic with modern hands? We’ll answer all these questions and more - plus there’s a FREE mosaic colouring sheet to entice the young artists in your charge. Alea iacta est!

See a real mosaic taking shape!

Have you ever wondered what it takes to design and lay a real mosaic by hand? We have three complete mosaics across our Roman villa site - and another to come!

In May, we’ll welcome back Dr Will Wootton and his students from King’s College London, who will be using traditional tools to recreate another mosaic in the corridor of our Roman villa.

This will be a rare and unique opportunity to see a real mosaic being laid, so if you’re looking for a last-minute school trip in May - this is your sign!

The mosaic team will be in from 4th May onwards for around two weeks, so do get in touch at schools@butserancientfarm.co.uk if you’d like to book your class in for an extra special visit.

What was it like to sleep in a Roman villa?

Head over to the Butser villa on a hot, summer’s day and you might think you’re in the Mediterranean. With its bright walls and cool interior, complete with the scent of herbs and flowers from the Roman garden, it can feel like the perfect spot for a holiday.

But when night draws in and the temperature drops, is it as idyllic as it looks? Find out in our two-part video series available on YouTube, as staff member Candice experiences a night alone in the Roman Villa!

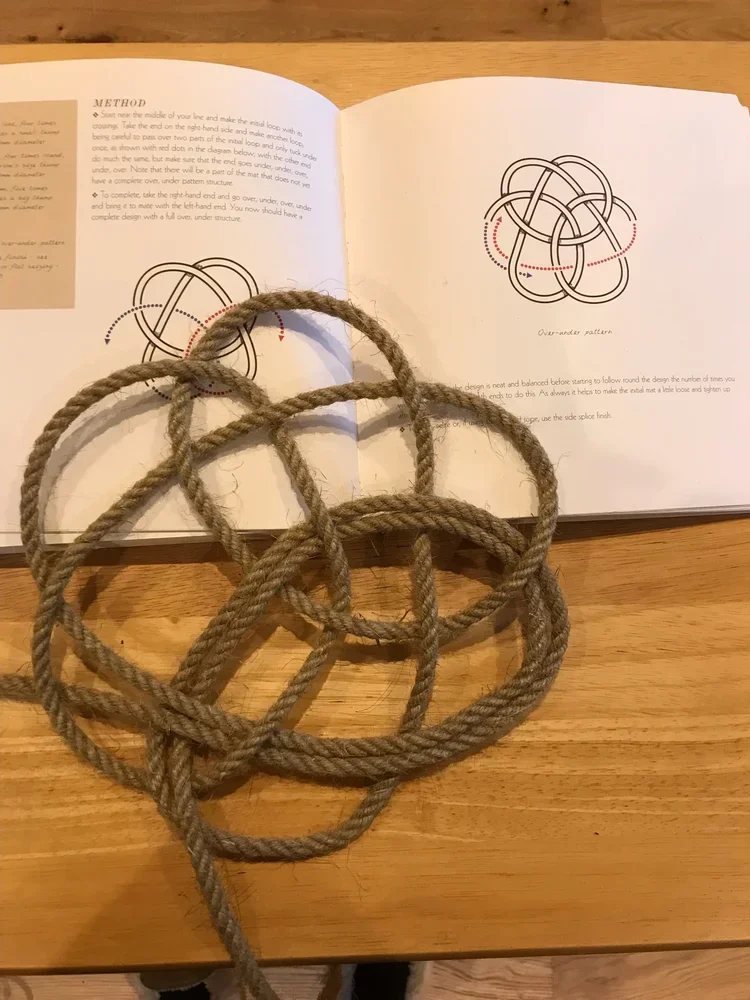

Free Mosaic Colouring Sheet

To celebrate the Romans this month, we’ve designed this colouring sheet based on the Sparsholt mosaic in our Roman villa. It is free to download, print and share for any educational, non-commercial purposes. Feel free to share your creations with us - we love to see them!

Top 10:

Roman Stories for Kids

We’ve put together a list of our favourite Roman stories for kids, from the streets of Pompeii to the gladiator ring.

Every purchase made from our Bookshop lists supports our work at the farm, so thank you!

In the news this week:

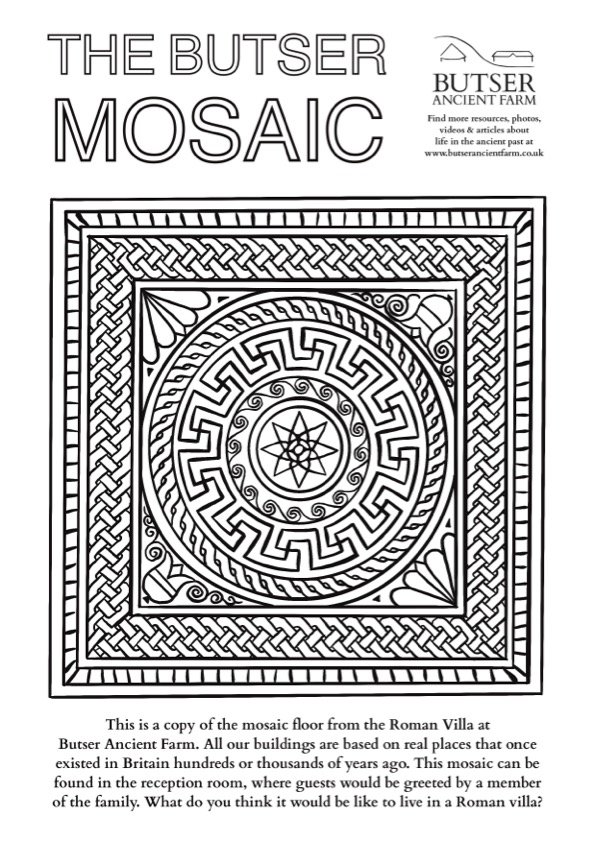

Largest ever Roman villa found in Wales

Archaeologists have unearthed the largest Roman villa ever found in Wales. It was discovered beneath a historical deer park, which means the land has never been ploughed or built on, so the villa remains are really well preserved.

This is a great way to talk to children about the process of archaeology and how we can use evidence to try and work out how people lived in the past. Here are some example questions and activities you could use to engage with the young minds in your classroom:

1. Archaeologists believe this could be a ‘grand estate’ where wealthy Romans might have lived. What sort of lifestyle do you think a wealthy Roman might have enjoyed? Would they have had plumbing and hot water, central heating, exotic food and drink, servants and luxury clothes?

2. Using the floorplan laid out by the archaeologists, could you guess which room was which? Where would the kitchen and bedrooms be? Would the house be facing towards or away from the sun?

3. Write a story about one of the children that might have lived here. What would they eat for breakfast? Who were their friends? What would they do when they were bored?

Tag us in your visit!

Thanks to Thornhill Primary School for tagging us in their recent visit! Year 3 had a great time with our team member Adrian to bring an end to their Stone Age topic - making jewellery, carving chalk, examining artefacts, and even squeezing in a quick visit to the Roman garden to see our newest mosaic up close!

Blog archive

- February 2026 5

- January 2026 6

- December 2025 2

- November 2025 2

- September 2025 1

- April 2025 2

- February 2025 1

- January 2025 1

- November 2024 2

- August 2024 1

- July 2024 2

- May 2024 1

- November 2023 1

- October 2023 1

- September 2023 1

- August 2023 1

- July 2023 1

- June 2023 2

- May 2023 2

- March 2023 1

- February 2023 1

- December 2022 1

- October 2022 1

- August 2022 2

- April 2022 1

- March 2022 2

- February 2022 1

- January 2022 1

- December 2021 2

- November 2021 3

- October 2021 2

- September 2021 5

- August 2021 2

- July 2021 3

- June 2021 3

- May 2021 2

- April 2021 4

- March 2021 1

- November 2020 1

- October 2020 2

- August 2020 1

- March 2020 4

- February 2020 4

- January 2020 3

- December 2019 3

- November 2019 1

- October 2019 1

- September 2019 1

- August 2019 1

- July 2019 6

- June 2019 3

- April 2019 2

- March 2019 3

- February 2019 2

- January 2019 1

- November 2018 1

- October 2018 2

- September 2018 3

- August 2018 4

- July 2018 2

- June 2018 2

- May 2018 2

- March 2018 6

- February 2018 1

- October 2017 1

- September 2017 5

- August 2017 4

- July 2017 3

- June 2017 1

- May 2017 1

- April 2017 3

- March 2017 2

- February 2017 3

- January 2017 1

- December 2016 2

- November 2016 1

- September 2016 1

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- June 2016 3

- May 2016 2

- April 2016 1

- March 2016 2

- February 2016 1

- January 2016 3

- December 2015 2

- November 2015 1

- October 2015 1

- September 2015 2

- August 2015 1

- July 2015 2

- June 2015 2

- May 2015 3