Frozen in Time: Coming Face to Face with Ötzi the Iceman

This week, our Experimental Archaeologist Therese Kearns shares a highlight from her recent trip to Italy, where she came face to face with Ötzi the Iceman.

View of the outside of the museum with alpine backdrop (Thérèse Kearns)

While planning a short break to Verona recently, I realised that Bolzano was only an hour and a half away by train. As an archaeologist, that proximity was irresistible: Bolzano is home to the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology where lies one of the most extraordinary archaeological discoveries of the 20th century - Ötzi the Iceman. I booked museum tickets immediately; there was no way I was going to miss the chance to encounter this remarkable Copper Age individual whose story continues to reshape our understanding of prehistoric Europe.

Ötzi was discovered in 1991 by two hikers in the Ötztal Alps, who initially assumed they’d found a lost mountaineer. The upper torso of a body was protruding from ice that had melted back after an unusually warm summer. Only when archaeologist Konrad Spindler examined the associated objects did the true age of the find become clear. The tools, the fragments of clothing, and the workmanship all pointed unmistakably to the late Neolithic or early Copper Age. Radiocarbon dating confirmed it: Ötzi lived more than 5,300 years ago.

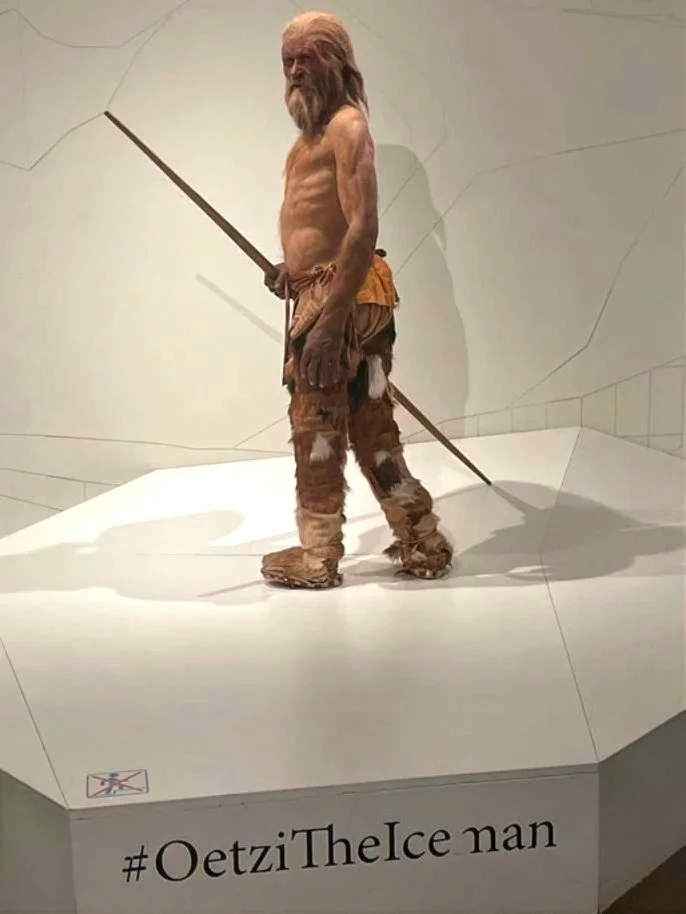

Reconstruction of Ötzi by the Kennis brothers, based on forensic methods. (Thérèse Kearns)

But the discovery wasn’t just the survival of a body - it was an entire time capsule. Alongside the mummy were his clothes, equipment, and a remarkable array of organic materials, preserved simply because they had rested in a cold, stable environment for millennia. Today, Ötzi lies in a purpose-built chamber kept at –6°C and 99% humidity, continuously misted with sterile water to mimic glacial conditions. The method is working well for now, but the conservation team remains cautious as no one knows how long it will remain effective.

I’d read extensively about Ötzi over the years and seen countless photographs, but nothing prepared me for the impact of seeing him and his belongings up close. The ingenuity and craftsmanship of his clothing and tools are truly striking.

His woven grass cloak, surprisingly sophisticated, would have offered excellent protection against wet conditions. His leather leggings, which were recovered in dozens of fragments and painstakingly reconstructed, stand as a testament to the skill and patience of the museum’s conservators.

Bearskin hat (South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology)

His shoes were beautifully made - fur-lined, built around an inner netting of tree bast that held insulating hay, wrapped in deer hide and fastened with leather thongs. His coat, crafted from alternating strips of goat and sheep skin cross-stitched together, forms a striking pattern of light and dark panels. And his bearskin hat which was stunning to see in person, completes the picture. Taken together, these items allow you to vividly imagine what it must have been like to meet this man as he journeyed through dramatic alpine passes more than five millennia ago.

Among his gear was the artefact I was most excited to see: his copper-bladed axe, one of Europe’s earliest known examples. I had studied this piece in detail during attempts to recreate the axe head in our hot-tech building, so seeing the original was genuinely thrilling. Scientific analyses reveal that the copper came from Tuscany, more than 400 km from where Ötzi was found - a clue to long-distance movement and exchange in the Copper Age.

We’re used to seeing prehistoric artefacts in museums and imagining their owners. With Ötzi, we can look directly at the person himself, which is extraordinary and unexpectedly emotional.

Twisted cord fragments (South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology)

Ötzi provides an unparalleled window into Copper Age life. He was likely in his mid-40s which is considered relatively old for his time. His body bore 61 tattoos, simple lines and crosses clustered around joints and areas of strain, strongly suggesting a therapeutic rather than decorative purpose. Some are still clearly visible as you peer through the small glass window into his chamber.

Scientific analyses have revealed he had a genetic predisposition to cardiovascular disease, lactose intolerance, Lyme disease, and the contents of his last meal, which included ibex, einkorn, and dried fruits.

We also know something of his dramatic final moments. A flint arrowhead lodged near a major artery, combined with severe head trauma, points to a violent end. Whether ambush, conflict, or something more personal, we may never know.

During my visit, I had the pleasure of speaking with Andreas Putzer, one of the museum’s curators. He described the surveys underway in the surrounding high-alpine regions. As glaciers retreat and temperatures rise, new artefacts are emerging - an exciting yet sobering prospect. The pace of discovery may well accelerate in the coming years, bringing both opportunities and serious challenges for conservation.

The South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology is superbly curated, with layered explanations, interactive reconstructions, and space devoted to ongoing research. But the true highlight is the quiet moment when you peer into the climate-controlled chamber. There, lying in the cold that has preserved him for over 5,000 years, is Ötzi.

Copper axe (South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology)

Woven cape (South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology)

Seeing his face is profoundly moving, an encounter like no other.

If you find yourself in northern Italy, go! Bolzano is an easy trip from Verona and well worth it. The museum sits in the beautiful old town, surrounded by cafés and narrow lanes, and inside it holds one of the most remarkable windows into Europe’s deep past.

The discovery site in the Ötztal Alps (South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology)